The EU lacks legitimacy (but it is not what you think)

A Democratic Mirage?

The predominance

of Brexit as a central topic within European politics for the past decade has

helped reveal an underlying issue that has dragged the European political

project down since its very first stages: how

legitimate are the decisions taken by the Union? Democracy in the EU

institutions has always been watched from a skeptical scope, and little to no

trust has been given to the process of decision making not only by the

political elites of the member states, but also by their inhabitants.

Procedurally, the

way legal acts of the Union are executed is similar to

many countries’ legislative process, involving several directly elected and

non-directly elected bodies such as the Parliament and the Council. Rather than

a perfect separation of powers, the EU works on a basis of institutional

balance. Despite how undemocratic that may sound, connections between legislative, executive and

judiciary are no different from those found in parliamentary democracies such

as the UK[1]. Efforts have also been

made to democratize the lawmaking process through new methods of

participative democracy such as the ECI

(European Citizens’ Initiative). Henceforth, EU citizens have the right to

directly propose pieces of legislation to the Commission, similarly to what happens in many countries such as Spain -article 87.3 of the Constitution rules how People's Legislative Initiative functions (ILP)-.

The rule of law

is always assured, and the treaties

regulate both the formal[2] and the substantive[3] aspects of European

legislation. On top, those same treaties that build the EU’s framework have

been accepted and transposed by every member state according to their domestic

legislation. And while it may be mathematically true that the six most

populated countries, having more than half of the MPs[4], could make some decisions

that affect the whole union the Parliament works on a partisan basis and

therefore it would be politically unachievable. Moreover, a multiparty system

has always been in place and thus compromises are to be made across the

political spectrum. The rest of the institutions? They work on an equal

representation basis for each member state.

Is the lack of legitimacy an insurmountable obstacle?

Nevertheless,

questioning the legitimacy of the EU decision making goes further than just

observing legislation and watching political and institutional reality. In

Lipset’s[5] words legitimacy is “[the]

capacity of a system to engender and maintain the belief that existing

political institutions are most appropriate for society”, and the EU is clearly

not achieving these expectations, at least not completely.

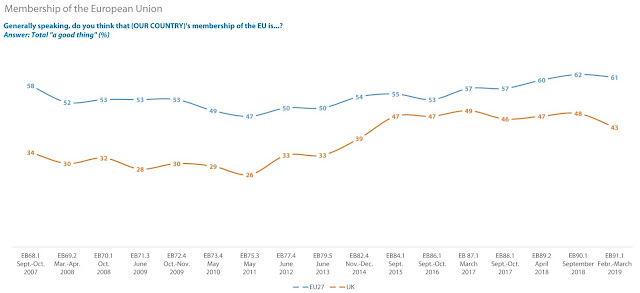

According to the

last

Eurobarometer, almost 40% of European citizens don’t see the EU as

a “good thing” for their home countries. Those numbers, rather than going down,

have been steadily increasing throughout the years. So much so that Eurosceptic

parties currently hold over 130 seats in the Union’s parliament.

Legitimacy,

according to Max Weber[6], is formed by three

aspects: the legal, the traditional and the charismatic base. We have seen how the European legal system not only reaches but also surpasses what are usually considered to be democratic standards. Still, the EU lacks the

last two. The traditional legitimacy is understood as immemorial respect to

the status of those exercising authority. And thus, the Union, as a political entity, goes anywhere from 60 to 30 years old regarding who you ask. Without ignoring the fact that some countries -as much as thirteen out of the current 28- have joined this sinking boat less than 16 years ago. On the other hand, charismatic legitimacy

refers to a devotion given to a concrete individual or institution due to its

current exemplary character or performance, something that is far from being a reality in such a faceless and distant institution. Many Europeans don't even know or are willing to understand the intricacies of the Union, and only a few would recognize a picture of Ursula Von der Leyen, Charles Michel or David Sassoli.

But even if those legitimacies might seem difficult to achieve, there is a deep-rooted European sociological order based on our historical common traditions. And that is key as a breeding

ground to construct them. When citizens are asked, not about EU institutions,

but about the togetherness of the European peoples, Europeanist-leaning

responses are way

more predominant. On average, over 80% reckon that we have more in

common than what sets us apart. And the difference from country to country is little, and consequently, it could be argued that solidarity amongst our peoples is pretty homogeneous.

In Habermas

terms, “we need a European public sphere”[7] in order to become real

European citizens. Democracy is not just a question of rules and individual

freedoms but also an issue of community. For it to exist, we need to help build European demos, a transnational

community with a set of political rules, historical roots, and common

institutions. Language is not a barrier -India, Switzerland, Belgium-, and nor is religion -Germany, The Netherlands-, or ethnic diversity -many African countries, USA-.

There are

several ways to achieve it. The EU electoral process feels just like 28 separate different elections and no transnational engaging is in place and many having been the proposes in order to turn this tide. For instance, the reformation of the

electoral system, by either having European parties running directly rather than national parties, or creating transnational lists that would serve to elect MEPs from a proportional European constituency, overlapping national ones. Other attempts of creating a citizen-tangible European arena have been on the table. The Spitzenkandidat

system, according to which each European party would present a candidate for

the Commission presidency throughout the campaign, was also a glimmer of hope,

that ended up disappearing into the bushlands of European bureaucracy, to the misfortune of Manfred Weber, who, as European People's Party, would have serve as President of the European Commission. Nevertheless,

the importance of the narrative on media and education are incontestable. The educational system has been always acknowledged to be the main dominant Ideological State Apparatus, throughout which countries shape collective consciousness and prevailing societal attitudes[8]. As

long as we don’t educate Europeans to understand the legal, sociological and

historical importance of the EU, no sense of community will be able to flourish

among the 27, preventing EU acts from seeming as legitimate as domestic ones.

In sum, legitimacy is not as easy as legislating and policymaking. Neither is it a given. And if the European project is wanted to succeed and not only remain intact but to develop and reach far beyond to improve the lives of the millions of citizens it comprises we need to proactively work towards a national and integrated Europe. Otherwise, the EU is doomed to failure.

[1]

Moellers C, Three Branches: a

Comparative Model of Separation of Powers (Oxford

University Press 2015)

[2]

Consolidated version of the Treaty of the Functioning of the European Union

[2012] OJ C 326/47 – Article 288 onwards regulate adoption procedures of the

legal acts of the Union.

[3]

The competences of the EU are regulated in both the TFEU and TEU.

[4]

Germany, France, UK, Italy, Spain and Poland comprise over 376

MPs out of 751

[5]

Lipset S M, Political

Man: The Social Bases of Politics (2nd ed.) (Heinemann, 1983) p. 64

[6]

Weber M, Politics as a Vocation (Fortress Press 1972)

[7]

Habermas J, ‘Democracy in Europe: Why the development of the

Eu into a transnational democracy is necessary and how it is possible’ (2015) European Law Journal

[8] Micheletti M, Political Virtue and Shopping: Individuals, Consumerism and Collective Action (Palgrave Macmillan 2010) p 74-75

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario